Managing heavy weather at sea

Yesterday, we addressed a conference of about 100 cruisers at the Irish Sailing Cruising Conference. In 2008, on a crossing of the north Atlantic, we encountered six gales and managed to avoid one strong storm. What we learned then, we were here to share about our experience with storm management. The conference was summarized overall in Afloat magazine.

Following is an overview of our talk:

When a weather window opened up, the Blackwells left Nova Scotia under

thick fog in about 15 knots of breeze. The fog persisted along the entire coast

of Newfoundland, which they never saw, until they crossed the Labrador Current.

Until then, they had sailed under full sail. Afterwards, the wind started to

build.

When a weather window opened up, the Blackwells left Nova Scotia under

thick fog in about 15 knots of breeze. The fog persisted along the entire coast

of Newfoundland, which they never saw, until they crossed the Labrador Current.

Until then, they had sailed under full sail. Afterwards, the wind started to

build.

They have several rules they go by:

Following is an overview of our talk:

Managing Offshore Storms

by Alex and Daria Blackwell

In 2008, Alex and Daria Blackwell left their jobs, loaded up their boat

and sailed across the Atlantic. They cruised Maine and Nova Scotia in Aleria, their Bowman 57 cutter rigged

ketch, before heading out to sea. Alex,

a master mariner and Daria, a licensed captain, had never crossed an ocean

before but had been sailing for many years, including weeklong coastal

passages, and did a great deal of preparation in advance.

But 2008 was an unusual year. Not only did the markets collapse around

the world while they were out at sea, the North Atlantic had more heavy weather

that year than would typically be expected. In the three weeks it took them to

sail across from Halifax to Westport, they experienced six gales and managed to

avoid one strong storm with potentially life threatening conditions. They

gained a good deal of experience on that crossing and have since crossed the

Atlantic twice more as well as having sailed to Scotland and Spain and along

the west coast of Ireland many times, never again seeing the type of weather

the North Atlantic had served up that year.

Since they survived, they were at the Irish Sailing Cruising Conference

to share what they had learned.

Daria first gave a general overview of how to think about the factors

that affect weather in the Atlantic. The ocean, being a conveyor belt for

water, has currents circulating around it. The Gulf Stream brings warm water up

the coast of the US that mixes with the cold Labrador current which brings cold

water and ice down from the Arctic. That continues to Ireland as the North

Atlantic Drift and then completes the loop with the Canary Current and North

Equatorial current.

Above the Atlantic sits the Azores High, a stable bubble of airmass.

Lows swoop down from North America and cyclones swoop up from tropical regions

where they form to circle around the Azores High. Of course Hurricane Ophelia

this year formed off the coast of Africa and headed directly North to Ireland

reminding us that climate change is making weather events less predictable and

more extreme. The trade winds also

circulate around this high pressure system creating the trade routes that,

together with the currents, enable ocean crossings.

Despite being an oversimplification, understanding weather patterns

during passage planning is essential. Many resources, like Passage Weather, are

available today to assist with planning a passage in advance. After departure,

however, other tactics are necessary.

It helps to develop a “weather eye” and keeping a log is important if

something untoward happens but is also vital to forcing awareness of changing

conditions. Timely response to changing conditions can mean the difference

between safety and comfort or survival management.

The Blackwells worked with the legendary Herb Hilgenberg, now retired,

who provided weather routing via SSB radio while they were underway. Herb

helped them interpret the forecasts for their region and provided suggestions

for the best routes to take advantage of the conditions and avoid undesirable

ones. It pays to enlist the help of shore-based experts to help interpret the

weather files, called GRIBS, one can download via SAT phone and SSB radio. There

are many services available.

When a weather window opened up, the Blackwells left Nova Scotia under

thick fog in about 15 knots of breeze. The fog persisted along the entire coast

of Newfoundland, which they never saw, until they crossed the Labrador Current.

Until then, they had sailed under full sail. Afterwards, the wind started to

build.

When a weather window opened up, the Blackwells left Nova Scotia under

thick fog in about 15 knots of breeze. The fog persisted along the entire coast

of Newfoundland, which they never saw, until they crossed the Labrador Current.

Until then, they had sailed under full sail. Afterwards, the wind started to

build.

1.

Stay on the boat – that means never leaving the companionway to go on

deck without being tethered to the boat. Sailing short-handed means that if

someone goes overboard, the likelihood of recovery would be slim.

2.

The time to reef is when you first think about it. Often people make

the mistake of waiting until conditions deteriorate when it becomes dangerous.

3.

Prepare in advance. Lack of preparation is an underlying factor in

disaster.

When the squalls started, they followed their direction and speed on

radar, but always made preparations in advance. Wind can go from 5 knots to 30

knots in seconds, and being caught unaware can result in a knockdown.

As the first gale approached, they had the following choices:

1.

Sail on

2.

Deploy a sea anchor or drogue

3.

Run with the wind

4.

Lie a-hull

5.

Heave to

As every boat is different, the Blackwells had experimented with

various methods and determined that heaving to in a storm situation to let the

storm pass over more quickly was their best bet on Aleria. Sailing on in a

storm is what racers do. This can cause a lot of stress on rig and crew. As cruisers

the Blackwells don’t subscribe to such discomfort.

Deploying a sea anchor puts great stress on deck hardware and can be

dangerous to deploy on a pitching deck and difficult to retrieve afterwards. In

addition, there is evidence that the stretching and contracting of the rode in

these extreme circumstances will cause internal abrasion in the fibres of the

rope, potentially leading to catastrophic failure.

Running with the wind under bare poles or storm sails would require

hand steering to manage the mountainous seas, and that would be difficult with

only two people. The motion of the wave cause the boat to yaw severely from

side to side. If the boat tends to surf down the waves it is possible that the

bow will become buried in the wave trough which would cause the boat to

pitch-pole.

Lying ahull in which all sail is removed and the boat is left to its

own defences was deemed most at risk of the vessel broaching and getting

swamped in massive seas.

They had experimented with heaving to under benign conditions and

decided that this would be their best option.

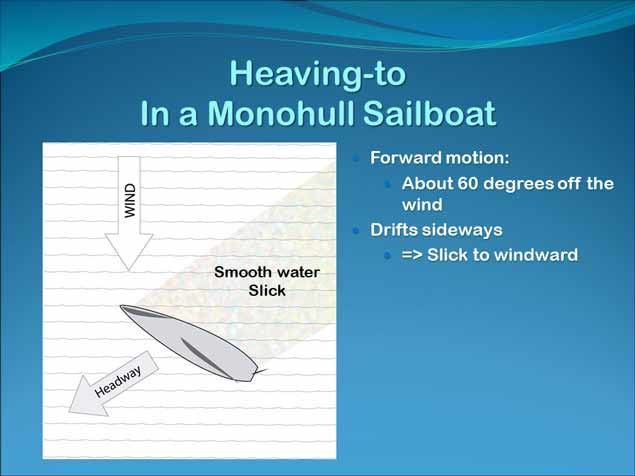

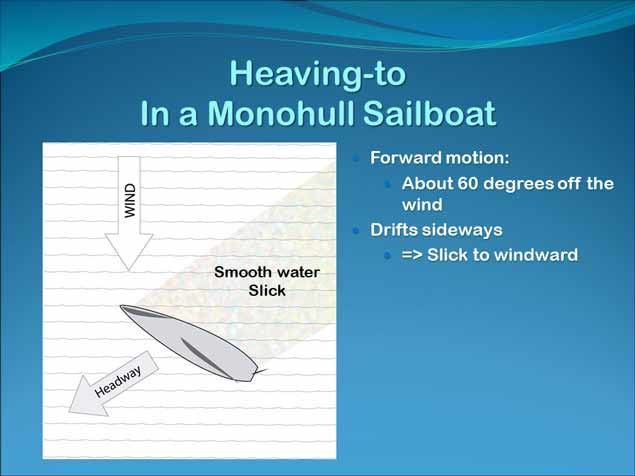

Heaving to on many boats is achieved by tacking after reducing sail and

not releasing the headsail sheet. The headsail is therefore backed and

counteracting the force of the main sail. The helm is lashed or locked to

windward. The boat settles down on an angle of about 60 degrees off the wind

sailing at about 1-2 knots, slipping sideways, creating a slick upwind and smoothing

the seas. When hove to, a degree of stability and calm is achieved that is

astounding.

The Blackwells sailed on through the first gale in which wind was in

the range of 35 knots gusting over 40. Their boat did well under staysail and

mizzen alone. When the wind built to more than 40 knots and the sea state built

to 30 feet with cresting waves and foam in the second gale, they opted to heave

to. For 36 hours, the gale raged overhead while they read books. After the

gale, they released the headsail sheet and then tacked through to get back on

course. The key here was to time manoeuvres with the seas. “We noted that waves

in this gale were coming in sets of 3 of about 20 feet and the 4th

would be an outlier of 30 to 40 feet. So we timed our tack for just after the

fourth wave to give us the best chance of not broaching if caught beam on.”

But the gales were unrelenting. They sailed through another and then

opted to heave to again. Half way through that gale Daria called out “I can’t

take it anymore, let me off at the next stop.” When Alex remarked that they had

forgotten to bring cookies along, Daria took to baking peanut butter cookies,

it was that calm aboard.

Daria explained that a quote by Donald Hamilton summed it up for her, “Being

hove to in a long gale is the most boring way of being terrified I know.”

Having a good library aboard made all the difference in the world.

On yet another occasion, heaving to may not have sufficed. Herb advised

the Blackwells to turn back and sail west for a day to allow a strong storm to

pass their track. With yet another gale approaching Alex being frustrated did

not heed the warning and sailed into the worst conditions they had experienced

yet, confirming that indeed the weather routers know what they are doing. Aleria hove to for a third time before

finally heading into Clew Bay.

The Blackwells explained that heaving to is not just useful in storm

situations. Heaving to can also assist with:

·

Reefing or dropping the mainsail

·

Making repairs in less challenging conditions

·

Adding fuel to the tanks

·

Having lunch in more peaceful conditions

·

Rendezvousing with a dingy

·

As a viable MOB manoeuvre

The most important consideration is to practice under benign conditions

to determine how your boat responds. Some vessels, like catamarans, heave to

best with one sail alone.

Several members of the audience confirmed the effectiveness of heaving

to. One experienced sailor told a story of being caught in a storm on a

delivery where the owner refused to heave to. He finally relented when

conditions became unbearable and now swears that it was the best thing he’s

ever learned.

An RNLI lifeboat crew member informed the group that he had just been

at a seminar in which the rescue helicopter service now request sailboats to

heave to on port tack if a rescue is underway because their equipment is

deployed from the starboard door. They have determined that heaving to is the

most effective means by which to stabilise the vessel and keep the mast from

getting caught up with their gear.

Participants were left thinking about their options and planning their

next opportunity to practice heaving to.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Alex is Rear Commodore for Ireland of the Ocean Cruising Club, a

Committee member and newsletter editor of the Irish Cruising Club and Committee

member of Mayo Sailing Club. Daria is Rear Commodore of the Ocean Cruising

Club. Alex and Daria are co-authors of Happy

Hooking the Art of Anchoring and Cruising

the Wild Atlantic Way.

Comments

Post a Comment